Translate this page into:

New physiotherapy device for interincisal mouth opening in oral submucous fibrosis patients: A pilot study

*Corresponding author: Ashish S. Bodhade, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology and Microbiology, Ranjeet Deshmukh Dental College and Research Centre, Nagpur, Maharashtra, India. ashishbodhade@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Bodhade AS, Dive AM, Raut AA. New physiotherapy device for interincisal mouth opening in oral submucous fibrosis patients: A pilot study. J Adv Dental Pract Res. 2024;3:10-4. doi: 10.25259/JADPR_30_2024

Abstract

Objectives:

It is estimated that 0.2–0.5% of Indians suffer from oral submucous fibrosis. The states of Gujarat, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra are the most severely impacted by this illness. Antioxidants, effective physiotherapy exercises, and topical corticosteroid injections are among the treatment options available for oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF). Despite being widely used, there are few studies assessing the effectiveness and patient compliance of the conventionally used technique for physiotherapy in patients with OSMF, such as ice cream sticks, tapered screws, and Heister jaw opener.

Material and Methods:

A device for physical rehabilitation that may be used at home was made using 3D printing technology. Ten patients participated in a pilot study that was carried out. These patients participated in the device’s pilot testing to assess the mechanical features and its ability to improve interincisal mouth opening, comfort (pain and control), and enjoyment. Comfort [Pain, comfort, control] with device use, ease of use [Portability] and satisfaction with device use.

Results:

A statistically significant (P < 0.0006) improvement in the mean mouth opening of OSMF patients was shown by quantitative data. After 1 month of use, there was a 1.8 mm difference in mouth opening. This implies that the device worked well for these people. Based on feedback, the majority of patients reported that the device was comfortable, easy to use, and showed satisfaction with the device use.

Conclusion:

It was found that people with OSMF can open their mouth more with the use of a new physiotherapy device. In addition to pharmacological therapy, this pilot study needs more investigation with a bigger sample size and a randomized control trial. Considering that this method of managing OSMF seems to be effective.

Keywords

Mouth opening device

Oral submucous fibrosis

Interincisal mouth opening

INTRODUCTION

Oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF), known as “Vidari” in ancient India, was one of the deceiving and chronic medical disorders that were first identified between 1000 and 800 BC. The ancient Indian physician and surgeon Sushruta is credited with the first documented description of this medical disease. He included it in his foundational work, the Sushruta Samhita. Schwartz J. presented the contemporary definition and characterization of OSMF in 1952. He described OSMF as “An insidious, chronic disease characterized by the deposition of fibrous tissue in the submucosal layer of the pharynx, palate, fauces, cheeks, oro-pharynx, and esophagus, and in the underlying muscles of mastication.”[1,2]

According to the World Health Organization, 4.96% of people worldwide have OSMF.[3] In India, the prevalence of OSMF has increased due to the prevalent practice of chewing areca, which varies from 0.03% to 6.42%.[4,5] Four out of every 1000 adults in rural India suffer from OSMF.[6]

In India, the estimated incidence of oral submucous fibrosis varies between 0.2% and 0.5%. Among the states most impacted by this illness are Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Bihar.[7] Typically, OSMF develops in people between the ages of 20 and 40.[7]

Treatment options for OSMF include topical corticosteroid administration, antioxidant use, and efficient physiotherapy exercises.[8]

Offering thorough at-home physical therapy routines for mouth-opening exercises are always in demand. These activities are essential for enhancing patients’ ability to speak and eat with their mouths, as well as for improving interincisal mouth opening (IIMO).[8-10]

Conventionally, patients with OSMF in stage I through III have long been advised to receive physiotherapy utilizing a stack of ice cream sticks placed as far posteriorly as is practical between the upper and lower teeth. Studies evaluating the efficacy and patient compliance of the ice cream stick approach for physiotherapy in patients with OSMF were scarce, despite its widespread use.

Consequently, there is an urgent need to create specialized equipment made just for OSMF patients. To maximize efficacy and patient comfort, these innovative devices should enable a regulated and gradual stretching of the oral tissues. They may also incorporate cutting-edge technology.

A device for at-home physical therapy was developed using 3D printing technology. A pilot study of ten patients was carried out. These patients participated in the device’s pilot testing to assess the mechanical features of the device, including its ability to improve interincisal mouth opening (IIMO), comfort (pain and control) and satisfaction.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

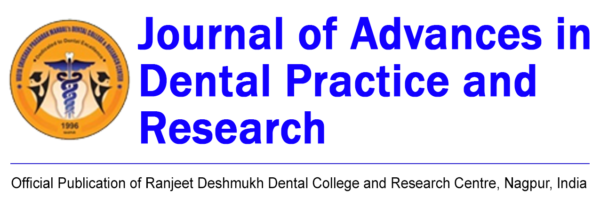

The strategy and design of the mouth-opening device were completed in cooperation with the engineering department and experts in biomedical devices. The biomedical device expert was shown the fundamental idea and design and had a discussion about it. The device’s strength, biocompatible material, cost-effectiveness, patient handling, device size, and mouth-opening mechanism were among the topics discussed. The device’s intended use was to treat OSMF, and 3D printing technology was used in its production. The finished product is ready for patient testing after numerous iterations [Figure 1].

- New device for interincisal mouth opening.

Pilot study methodology

Devices were provided to ten clinically diagnosed cases of OSMF stage I–III, based on Khanna and Andrade classification, following approval from the Institutional Ethical Committee. Informed consent was obtained before enrolling these patients. Patients were instructed to give up chewing areca nut; local application of triamcinolone acetonide ointment twice daily was prescribed; oral antioxidant was prescribed once daily; and a novel physiotherapy equipment was prescribed to be used twice daily for 15 min each for a month. This combined medication therapy approach was used in accordance with Patil et al.[11] Patients’ baseline parameters, such as IIMO, were recorded using a Vernier caliper [Figure 2]. Patient comfort (pain and control) and device satisfaction (feedback received after using the device) were also solicited. Following a follow-up visit after 1 month, the same parameters were recorded. To assess the effectiveness of the device in mechanically increasing mouth opening, a comparison of the IIMO was made between the initial visit and 1 month later.

- Interincisal mouth opening measurement in oral submucous fibrosis patient using Vernier caliper.

RESULTS

Results of pilot testing show observable improvement in IIMO in device user after 1 month. Maximum patients showed comfort, ease of use, and satisfaction after using the device. Strengths and weaknesses of the device were also identified during this phase.

The age range of the study patients was 21–60 years old, with an average age of 35.5 years. Men (70%) outnumbered women (30%). OSMF Stage I (20%), Stage II (70%), and Stage III (10%) were the clinical stage distribution [Table 1].

| S. No. | Age | Sex | Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 21 | M | OSMF I |

| 2. | 22 | M | OSMF II |

| 3. | 30 | M | OSMF II |

| 4. | 26 | M | OSMF II |

| 5. | 36 | F | OSMF II |

| 6. | 40 | M | OSMF I |

| 7. | 20 | M | OSMF II |

| 8. | 60 | F | OSMF II |

| 9. | 55 | M | OSMF III |

| 10. | 45 | F | OSMF II |

OSMF: Oral submucous fibrosis

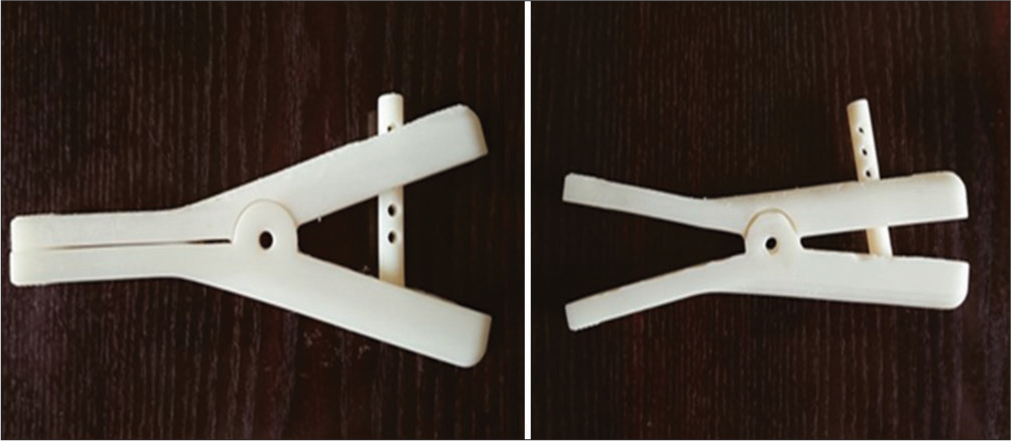

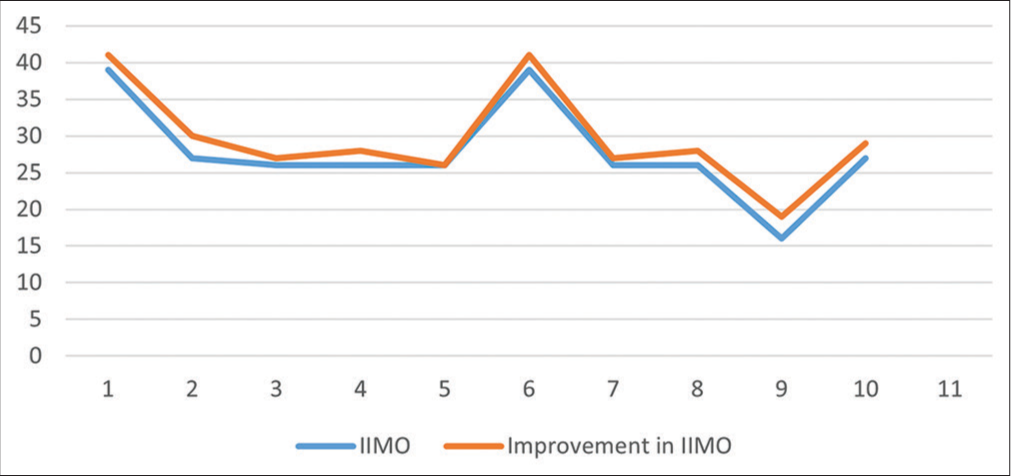

The mean mouth opening of OSMF patients improved, according to quantitative data, and this improvement was shown to be statistically significant (P < 0.0006).

After using the device for a month, a 1.8 mm difference in a mouth opening was discovered.

This indicates that the device worked well for these people [Tables 2 and 3, Graphs 1 and 2].

| Improvement in IIMO at First Visit | Improvement in IIMO after 1 month follow-up |

|---|---|

| 39 | 41 |

| 27 | 30 |

| 26 | 27 |

| 26 | 28 |

| 26 | 26 |

| 39 | 41 |

| 26 | 27 |

| 26 | 28 |

| 16 | 19 |

| 27 | 29 |

IIMO: Interincisal mouth opening

| IIMO | Mean IIMO and SD | N | Improvement in IIMO after 1 month follow-up | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean mouth opening at baseline/first visit | 27.8 ± 4.171 SD | 10 | 1.8 mm | *P-value 0.00016 [t-value 3.1942] |

| Mean mouth opening at follow-up visit after 1 month | 29.6 ± 4.155 SD | 10 |

- Distribution of improvement in interincisal mouth opening (IIMO) before and after device use.

- Improvement in mean interincisal (IIMO) mouth opening in device user after follow up visit.

In this case, comfort with device use refers to the patient’s being questioned about any pain they may be experiencing, including tissue, tooth, and temporomandibular joint dysfunction pain. The majority of patients (90%) said that they felt comfortable using the physiotherapy device [Table 4, Graph 3].

| Response | N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comfortable | Y | 9 | 90 |

| Uncomfortable | N | 1 | 10 |

| Total | 10 | 100 |

N: Total number of responses, Y: Comfortable to use, N: Uncomfortable to use.

![Comfort [Pain, comfort, control] with device use. (Y: Comfortable to use, N: Uncomfortable to use.)](/content/142/2024/3/1/img/JADPR-3-010-g005.png)

- Comfort [Pain, comfort, control] with device use. (Y: Comfortable to use, N: Uncomfortable to use.)

Patients were questioned about how simple it was to handle and transport the physiotherapy device. About 90% of patients said using the device was simple, while one patient did not find it easy [Table 5, Graph 4].

| Response | N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ease of use present (Portability) | Y | 9 | 90 |

| Ease of use absent (Portability) | N | 1 | 10 |

| Total | 10 | 100 |

Y: Ease of use present, N: Ease of use absent, N: Total no of response

![Ease of use [Portability]. (Y: Comfortable to use, N: Uncomfortable to use.)](/content/142/2024/3/1/img/JADPR-3-010-g006.png)

- Ease of use [Portability]. (Y: Comfortable to use, N: Uncomfortable to use.)

A question concerning overall device satisfaction was posed. A maximum of 80% of patients expressed satisfaction with their use of the device, compared to 10% who expressed negative satisfaction and 10% who were unable to respond [Table 6, Graph 5].

| Response | N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction | Y | 8 | 80 |

| Satisfaction | N | 1 | 10 |

| Can’t say | U | 1 | 10 |

| Total | 10 | 100 |

Y: Satisfied, N: Not satisfied, U: Can’t say/No response, N: Total no of response

![Satisfaction with device use [Device feedback].](/content/142/2024/3/1/img/JADPR-3-010-g007.png)

- Satisfaction with device use [Device feedback].

Summary of the interpretation of the results

The mean mouth opening of OSMF patients improved, according to quantitative data, and this improvement was shown to be statistically significant (P < 0.0006).

After using the device for a month, a 1.8 mm difference in mouth opening was discovered.

This indicates that the device worked well for these people.

Based on feedback, the majority of patients reported that the device was easy to use (90%) and comfortable (80%), and that they were satisfied with it (80%).

DISCUSSION

Oral submucous fibrosis is a precancerous condition that is becoming more common in the Indian subcontinent. It is caused by chewing areca nut or areca nut mixed with tobacco with a estimated incidence rate of 0.4%. Early OSMF discovery is critical because it allows for timely treatment to halt the disease’s progression and possibly fatal consequences, like oral cancer.

To control OSMF, a variety of therapeutic modalities have been studied; some have shown promising results in reducing the progression of the disease and even partially reversing its effects. These therapeutic approaches include pharmaceutical interventions such as the use of corticosteroids, antioxidants, and other anti-inflammatory drugs, in addition to nonpharmacological strategies, including physiotherapy and dietary modifications.[12]

With participants ranging in age from 21 to 60, OSMF is generally observed in the 35.5-year-old age group in the present study. The outcomes matched those of studies by Pandiar et al.[13] and Hazarey et al.[14] However, according to Hazarey et al.,[14] OSMF has recently become increasingly prevalent in a younger age range.

Based on the study’s gender distribution, men were found to have an increased risk of OSMF compared to women. This is consistent with earlier studies, as the ones carried out by Hazarey et al.[14] Male-to-female ratio of 4.9:1 was reported by Hazarey et al.[14]

In the present study, OSMF stages I (20%), II (70%), and III (10%) made up the clinical stage distribution.

The improvements in IIMO found in this study were statistically significant (P < 0.005). This showed how well the PT equipment functioned for the patients with OSMF in this pilot study group. This improved that mouth openness was 1.8 mm more than it was before physiotherapy began.

Various physiotherapy modalities have been found to be helpful at various OSMF phases. The applied procedures’ efficacy, mobility, comfort, satisfaction, and ease of use were not assessed, though. The goal of the present study was to show how the study tool, which was built especially for physiotherapy exercises like stretching the oral mucosa in patients with OSMF, works.

A small number of research have employed mouth-opening devices; Patil et al.’s study is one of note.[11] Every patient in the experimental group received an ice cream stick workout regimen, oral antioxidants, and clobetasol propionate corticosteroids. Each of the two subgroups – mouth exercising device Group A and non-mouth exercising device (MED) users’ Group B – consists of three individuals. The MED seems to aid in improving oral opening in patients with OSMF when used in conjunction with local injection and/or surgical treatment.

Li et al.,[15] after utilizing the reasonably priced EZ Bite device, mouth opening and oral health quality of life (OHQOL) greatly improved. There are certain flaws to this study, including an incomplete explanation of the design. There was no medication given. It is unknown if patients with oral cancer who have trismus receive treatment.

Reddy et al.,[16] the device owned by Shekar was used. Three OSMF patients used the equipment throughout their physiotherapy sessions. To improve mouth opening in patients with OSMF, oral physiotherapy induces tissue remodeling. Other physiotherapy techniques, such as mouth opening with therapeutic ultrasound and microwave diathermy, have been found to be successful. Dani and Patel,[17] and Shahbaz et al., mucosal flexibility is increased by improved circulation, submucous fiber separation, and local tissue reorganization brought about by the MED.[18] The scientists have found that when oral antioxidants and topical triamcinolone 0.1% are taken together, the MED helps that patients with OSMF enhance their interincisal distance.[18] The reviews author, Gondivkar et al., gathered the research done between 1996 and 2019. Important observations in this review were that the conclusions of said mode of action were not supported by pathophysiological alterations at microscopic as well as molecular levels.[19] The author listed the benefits and drawbacks of several mouth-opening tools (MEDs).

CONCLUSION

In early stage OSMF patients, the current pilot study demonstrated efficacy in enhancing IIMO. Further, research is required to examine the device using a larger sample size and a more robust study methodology.

Ethical approval

The research/study approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee at VSPM Dental College and Research Center, Nagpur, number ECR/885/Inst/MH/2017, dated January 01, 2018.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Alka Dive is on the Editorial Board of the Journal.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Oral submucous fibrosis: Etiology, pathogenesis, and future research. Bull World Health Organ. 1994;72:985-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- Proposed clinical definition for oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2019;9:311-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Update from the 5th edition of the World Health Organization classification of head and neck tumors: Tumours of the oral cavity and mobile tongue. Head Neck Pathol. 2022;16:54-62.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of oral submucous fibrosis: A review. Int J Oral Health. 2017;3:126-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of oral submucous fibrosis among habitual Gutkha and areca nut chewers in Moradabad district. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2014;4:8-13.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Operational guidelines national oral health program. 2012. :21. Available from: http://www.mohfw.nic.in/writereaddata/l892s/51318563751452762792.pdf [Last accessed on 2024 May 29]

- [Google Scholar]

- Physiotherapeutic approach in oral submucous fibrosis: A systematic review. Cureus. 2023;15:e48155.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Conservative management of oral submucous fibrosis. Asian J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;17:26-30.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Interventions for the management of oral submucous fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;4:CD007156.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A systematic review of medical interventions for oral submucous fibrosis and future research opportunities. Oral Dis. 2011;17(Suppl 1):42-57.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A randomized control trial measuring the effectiveness of a mouth-exercising device for mucosal burning in oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122:713-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oral submucous fibrosis: A contemporary narrative review with a proposed inter-professional approach for an early diagnosis and clinical management. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;49:3.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Correlation between clinical and histopathological stagings of oral submucous fibrosis: A clinicopathological cognizance of 238 cases from South India. Cureus. 2023;15:e49107.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oral submucous fibrosis: Study of 1000 cases from central India. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:12-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mouth-opening device as a treatment modality in trismus patients with head and neck cancer and oral submucous fibrosis: A prospective study. Clin Oral Investig. 2019;23:469-76.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Novel physiotherapy appliance in the management of oral submucous fibrosis. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2021;33:91-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The effectiveness of therapeutic ultrasound in patients with oral submucosal fibrosis. Indian J Cancer. 2018;55:248-50.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effectiveness of a mouthexercising device in adjunct to topical steroid and antioxidants in OSMF-A clinical study. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2022;34:405-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical efficacy of mouth exercising devices in oral submucous fibrosis: A systematic review. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2020;10:315-20.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]